Health insurance premiums rise dramatically with age in the United States. This is not a theoretical risk or a pessimistic/overly conservative assumption. It is a core feature of the healthcare system, explicitly permitted under the Affordable Care Act.

The earlier someone retires, the longer they are exposed to predictable, age-driven increases in healthcare costs before becoming eligible for Medicare. That rising liability must be funded somewhere, and traditional planning rules of thumb, like the 4% rule, do not account for situations like this.

The FIRE community seems to sense this. Healthcare consistently ranks as one of the most anxiety-inducing and least well understood aspects of early retirement.

This article argues that healthcare costs in early retirement are not simply “higher than expected,” nor are they primarily an inflation problem. They are guaranteed to rise with age, peak just before Medicare eligibility, and then fall sharply once Medicare begins. Any withdrawal strategy that assumes spending grows uniformly with CPI, without specifically carving out healthcare costs, is incomplete and far more risky than traditional rules of thumb state.

Using my own household as an example, I will show how to model healthcare costs.

I will explain why younger retirees, lean and traditional FIRE households in particular, face materially more risk than is commonly acknowledged. I will also show that this risk is finite, quantifiable, and manageable with the right framework.

Along the way, I will address several related questions that the FIRE community increasingly grapples with:

- Why age-based ACA pricing creates a predictable “healthcare hump” before Medicare

- Why it is risky to assume long-term ACA subsidies as a foundational planning input

- Why lean and traditional FIRE are more exposed to this risk than chubby or fat FIRE

- Why alternatives such as self-insurance, healthshares, and catastrophic-only coverage are gaining attention

- And how to translate this analysis into a more realistic FIRE target without abandoning rational optimism

The central conclusion is uncomfortable but straightforward:

If you retire early and intend to maintain traditional health insurance through age 65, you need a larger buffer than traditional retirement rules suggest, solely to account for the guaranteed rise in healthcare costs.

The younger you retire, and the leaner your target, the more important this adjustment becomes.

This analysis does not assume healthcare costs rise faster than inflation. It does not rely on worst-case scenarios. It simply takes the existing rules of the system seriously and follows their implications.

Early retirement is a privilege. Planning for it responsibly means acknowledging its unique risks rather than hoping they resolve themselves.

The Common Starting Point: ACA Coverage in Early Retirement

Many early retirees in the United States assume that ACA coverage will bridge the gap between early retirement and Medicare eligibility. As a short-term mechanism, this is reasonable. ACA plans are available regardless of employment or pre-existing conditions.

Within the FIRE community, people tend to prioritize catastrophic protection over low deductibles, making Bronze or Silver plans the most common choice for the healthy and able-bodied portion of the FIRE community who choose to continue with traditional health insurance.

The problem is not that ACA coverage exists. The problem is how it is typically modeled.

Premiums vary widely by state and county, and unsubsidized pricing in many markets is already substantial, even for younger households. Here is an example range for health insurance plans, by state, for a family like mine, with two adults aged 35 and two young children:

Unsubsidized ACA Premiums at Age 35 (Family of Four)

- Connecticut (Bridgeport): ~$24k–$28k

- New Hampshire (Manchester): ~$10k–$12k

- Colorado (Highlands Ranch): ~$13k–$16k

You can quickly get estimates of this sort using a free tool like KFF’s Health Insurance Marketplace Calculator.

The premiums above are representative of current benchmark pricing for my family. I chose these three state examples because when it comes to premium costs, Connecticut is one of the more expensive states, New Hampshire is among the cheapest states, and Colorado is where I actually live (in the lower half in terms of cost).

These expenses are likely what many early retirees expect and feel they understand. In some cases, they may even appear lower than anticipated, particularly for those accustomed to seeing the full, unsubsidized cost of employer-sponsored coverage for the first time.

The risk is that these age 35 premium levels are often treated as a stable, long-term planning assumption. Under the ACA’s age-based pricing structure, that assumption is incorrect.

Premiums are legally permitted to rise substantially as households age, meaning that costs which appear manageable in early retirement can grow materially over time. Most FIRE plans implicitly anchor to these early-year figures, without explicitly accounting for the predictable increases that follow.

Age-Based Pricing and the Non-Negotiable Shape of Healthcare Costs

The ACA prohibits pricing based on health status. It explicitly allows pricing based on age.

Federal rules permit insurers to charge older enrollees up to three times more than younger ones. This creates a healthcare cost curve that is not speculative, cyclical, or optional. It is structural.

That structure produces a predictable trajectory:

- Costs rise steadily through the 40s

- Accelerate materially in the late 50s and early 60s

- Peak just before Medicare eligibility

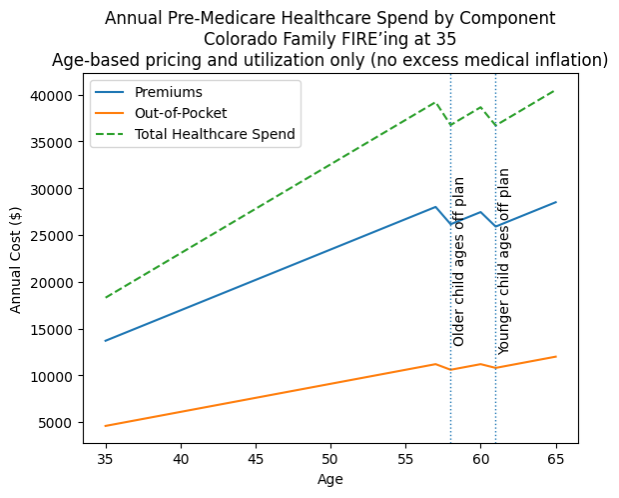

The chart above estimating costs for my family illustrates this clearly:

- Annual spend rises from the mid-teens to approaching $40,000.

- Two step-downs occur as my children age off our household plan

- Despite those step-downs, total costs resume rising sharply due to older adult pricing

This increase is not driven by excess medical inflation. The increase is driven by age-based pricing and utilization alone.

Any withdrawal strategy that does not explicitly make room for this is incomplete. The 4% rule, specifically, assumes that spending stays in line with inflation. It does not account for the reality of healthcare – where a material portion of spending rises much faster than inflation.

A family like mine that wants to spend $100K per year is really saying that they want to, “spend $82K per year on everything that isn’t healthcare, with an $18K allotment towards healthcare.”

To keep the rest of one’s living expenses constant at $82K adjusted for inflation, we need something materially more than the $2.5M suggested by the 4% rule to cover healthcare costs.

You may have heard that spending declines dramatically in traditional retirement. JP Morgan has a famous study to this effect showing spending gradually declining nearly 30% from age 60-85. However, this study examines spending for older adults. This is not likely to reflect the pattern of spending in a household like mine, with two adults in their 30s and two young children.

My spending will likely follow this same curve – declining from age 60-85, but I will not forecast this spending reduction “smile” to an early retirement for the next 30 years. I think many/most reading this will also find that too aggressive an assumption.

Note that at least two states (VT and NY) do not allowACA plans to factor age into premium pricing. In those states, the 4% rule planning does apply (though I still think that out of pocket expenses are likely to rise as one ages and should be accounted for). Forecasting is therefore simpler, though VT and NY residents will be starting with much, much higher premium costs than the rest of the country in the early years of their early retirement as a result, near the very top of the curve for my household in Denver as I approach my late 50s.

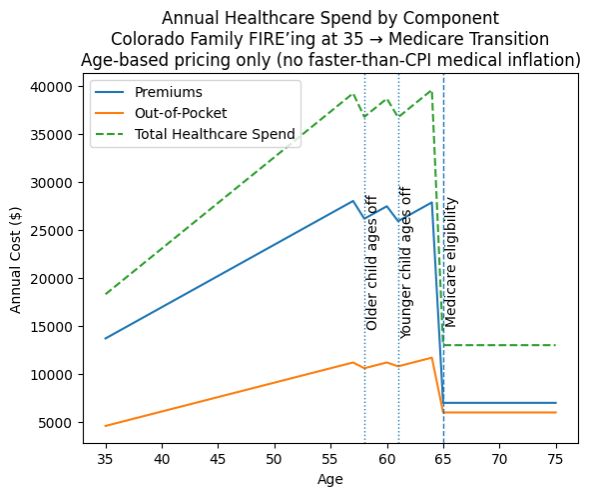

This Cost Escalation is a “Bridge to Medicare”, not a permanent increase

The healthcare cost escalation described earlier is best understood as a bridge to Medicare issue, not a permanent condition of early retirement.

In the cost projection model for my household, the change at age 65 is huge. Premiums tied to ACA age-based pricing disappear, and total healthcare spending drops sharply. This is good news. Medicare’s cost dropoff is a meaningful offset to the healthcare premium cost escalation issue here.

For FIRE planning purposes, this means the goal is not to fund permanently higher healthcare spending. The goal is to simply fund the “bridge to medicare”. Withdrawal strategies that account for this reality look very different from those that assume healthcare spending grows in line with inflation forever.

In other words: We do not need to increase our portfolio size to accommodate some baseline higher level of spending. We instead need to fund a very specific cost, in a very specific window of early retirement.

Funding this risk is much more like planning to pay for college education for two children than it is like sustaining a lifestyle permanently on the 4% rule.

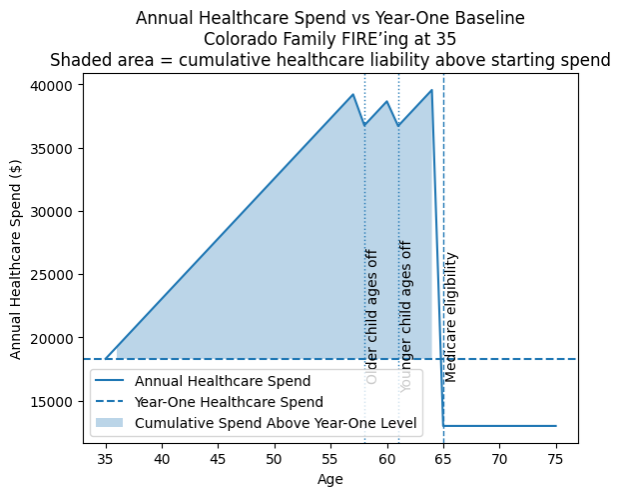

The Core Planning Implication: Buffer your “4% Rule FIRE portfolio” by the area under the curve:

I can reasonably project my annual spending for healthcare at ~$18,300 per year for my family of four in 2026, assuming no ACA subsidies. That number may fluctuate, and a more conservative forecaster may wish to assume higher out of pocket costs. But, as a baseline, this is reasonable starting point.

To account for just how much more I need to accumulate to “FIRE” at the 4% rule, I need to add up the area under the curve, highlighted in blue. Specifically, I sum the difference between this baseline healthcare assumption and the projected premiums and out of pocket expenses at each age. I do this for every year until age 65, when I become eligible for Medicare. The result tells me how far short of my FIRE target I truly am if I rely solely on the 4% rule.

In this example, the shortfall is about $378,000.That is the amount I need to bridge, on top of my 4% rule FIRE portfolio.

The most straightforward way to address this is to simply add that amount to my FIRE number. If my original target was $2.5M to support $100K of annual spending, I could increase that target to $2.88M.

However, that is likely too conservative. Because healthcare costs increases are most acute later in early retirement, an invested portfolio should have time to earn real returns before the bulk of this spending is required. Assuming a conservative 2% real return, an additional $250K is enough to cover the difference. Obviously, this amount will vary person to person and household to household.

In the context of a $2.5M FIRE portfolio, this difference is unlikely to be a dealbreaker. At this point and beyond, as we get into Chubby of FatFIRE levels of wealth, healthcare cost escalation is a manageable risk, that needs to be considered, but also one that is unlikely to be a fundamental barrier to early retirement.

This risks are far more acute for Lean FIRE, Barista FIRE, or other plans built on relatively small portfolio balances. Annual inflation-adjusted healthcare costs approaching $35,000 in one’s early 60s just don’t work with a $1M starting portfolio balance. Bridging this gap may require 25%-40% more wealth than originally planed, and potentially more in higher cost states. That’s a real threat to FIRE.

And yes, as uncomfortable or absurd as $35,000 per year, just for healthcare costs, in a relatively low cost state like Colorado may seem, that is the current reality of unsubsidized healthcare costs for people in their early 60s in the United States.

Why Long-Term ACA Subsidies Are a Risky Planning Assumption

You may have noticed I have not factored in ACA subsidies so far. That’s intentional.

Many FIRE plans implicitly rely on the assumption that ACA subsidies will materially offset rising healthcare costs for decades, even for millionaire households. I think this is a very aggressive planning assumption.

Unlike Medicare, ACA subsidies are not a universal entitlement. They are a policy mechanism funded by taxpayers and designed to expand healthcare access for lower income households. Relying on them over a decades-long early retirement implies several specific assumptions:

- Future taxpayers will willingly subsidize healthcare for households with high net worth but low reported income and the ability to work

- Subsidy formulas will remain favorable despite rising fiscal pressure

- Political coalitions will continue to support this structure for decades.

These assumptions may prove true. But, I do not believe this is a neutral base case. I think this is a very specific political bet that many in the FIRE community are making.

Subsidies may persist. They may not. They may even expand again. But treating them as a foundational assumption rather than a contingent upside is a huge risk. It may be reasonable to plan on them in the initial years of early retirement. But, I think it’s irresponsible to rely on them in a base case.

A strong FIRE plan should survive without subsidies. If subsidies exist, they improve outcomes. If they do not, the plan still needs to work.

Geographic Arbitrage, Part-Time Work, and Other Mitigators

Geographic arbitrage can meaningfully lower baseline healthcare premiums. Part-time work can provide access to employer sponsored coverage. Some households will experience low healthcare needs for long time periods. All of these are real and legitimate ways to reduce healthcare costs.

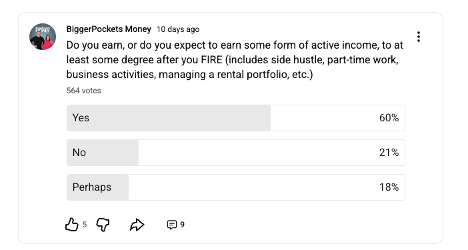

Many early retirees expect to use at least one of these levers. Survey data from the BiggerPockets Money community suggests that nearly 80% of respondents either plan to earn, or are open to earning, some form of active income in early retirement. I count myself among them. These strategies are common, practical, and often effective. And yes, it’s still FIRE if you choose to work in some capacity in your early retirement.

However, none of these mitigators change the underlying problem:

- Age-based pricing still dominates

- Costs still rise sharply before Medicare

- Political risk remains asymmetric

Geographic arbitrage and various forms of work to create additional income or cover health insurance should be treated as risk mitigators, not pillars. If financial independence is a continuum, then one extreme should be no requirement to earn another dollar of active income for the duration of one’s life.

Alternatives to Traditional Health Insurance (and Why Interest Is Growing)

As healthcare costs increasingly dominate late-stage early retirement risk, it is not surprising that many in the FIRE community are exploring alternatives to traditional comprehensive health insurance.

To be clear at the outset: none of these options are obvious replacements for ACA coverage, and all involve meaningful tradeoffs. However, the fact that they are being discussed more seriously is itself informative. It reflects a growing recognition that the current system concentrates too much retirement risk into a single, expensive, and policy-dependent expense category.

Broadly, these alternatives fall into three categories:

1. Partial or Full Self-Insurance

At one end of the spectrum is explicit self-insurance.

This approach accepts higher routine medical costs out of pocket while reserving portfolio protection primarily for catastrophic events. In practice, this might mean paying cash for most care, negotiating prices directly, and maintaining a large, earmarked healthcare reserve within the portfolio.

The appeal is straightforward:

- It removes exposure to escalating premiums.

- It reduces dependence on subsidy rules and income thresholds.

- It aligns healthcare risk more directly with net worth.

The drawback is equally clear. Healthcare costs are not merely volatile; they are fat-tailed. A single adverse event can produce six- or seven-figure liabilities. Fully self-insuring against that risk requires a level of wealth and risk tolerance that exceeds what most early retirees possess.

The Expected Value calculation for self-insurance, however, is likely to continue to grow relative to other forms of insurance until some event triggers a reset of healthcare costs in America.

2. Healthshares and Similar Arrangements

Another increasingly discussed option is participation in healthshare organizations or similar cooperative arrangements. I am part of a healthshare personally, in large part the result of the many hours of research on this topic that led to this article and other work studying healthcare costs in early retirement. I am also fortunate to have good health, and have family members in good health.

These structures typically offer much lower monthly costs than ACA plans, particularly for younger and healthier participants. In exchange, they introduce a different risk profile: discretionary coverage decisions, non-contractual obligations, eligibility constraints, and governance risk.

From a planning perspective, the tradeoff is not simply cost versus coverage. It is regulatory certainty versus affordability.

Healthshares can reduce near-term cash outflows materially. But they shift risk from insurers to participants in ways that are difficult to model probabilistically. Coverage rules can change. Claims can be denied. Large-scale stress events can overwhelm the system. I factored these risks into my decision, and I am uncomfortable with my choice to be part of a healthshare, rather than traditional insurance. I’d just have to believe some pretty unrealistic probabilities to be better off with traditional insurance.

For FIRE households that prize predictability and robustness, this uncertainty is likely to be as uncomfortable as it is for me, even if the economics are tempting.

3. Catastrophic Medical Liability Coverage

A third category, and one that may grow in importance, is the idea of separating catastrophic risk from routine healthcare entirely.

Conceptually, this resembles liability insurance rather than traditional health insurance. The individual covers routine care and moderate expenses out of pocket, while purchasing protection against extreme medical debt above a defined threshold.

For example, a policy might activate only after the insured has paid the first $25,000 or $50,000 of annual medical costs, with the insurer covering catastrophic liabilities beyond that point.

The appeal of this structure is that it targets the specific risk that most threatens portfolio sustainability: unbounded downside. It also avoids many of the inefficiencies of comprehensive insurance, where high premiums are paid to pre-fund relatively predictable expenses.

At present, this market is limited and underdeveloped. If I could find a policy of this type, I would sign up immediately, but I am not aware of one offered in my state. Regulatory constraints, adverse selection, and unclear pricing will all slow adoption even if options do pop up. But the economic logic is compelling, particularly for higher net worth early retirees who can comfortably absorb routine costs but want protection against tail risk.

I really like this as a concept for the FIRE community, but it does not exist in practice in a way that I can access right now. Perhaps, if enough people read this and express serious intent, we can form some kind of group or true business/insurance venture to make this happen. If you have serious interest or capabilities in making this happen, please email me at Scott@biggerpocketsmoney.com.

Why These Alternatives Matter for FIRE Planning

It is important to emphasize that none of these options are panaceas. Each introduces new forms of risk, complexity, or uncertainty. When a single expense category grows large enough to materially lower safe withdrawal rates, there will be sustained pressure to restructure, offload, or isolate that risk.

Traditional health insurance is designed around employment, not early retirement. As long as that mismatch persists, experimentation around the edges is inevitable.

From a planning perspective, these alternatives are best viewed as risk management tools, not assumptions. They may reduce costs, create optionality, or provide fallback strategies if premiums rise faster than expected. But they should be layered on top of a conservative base plan, not used to justify aggressive withdrawal rates.

Concluding Thoughts

Healthcare costs in early retirement are not an uncertainty to be hoped away. They are a core feature of the system, rising predictably with age and peaking just before Medicare eligibility.

Ignoring that structure leads to overstated safe withdrawal rates. Healthcare is a core expense that cannot be modeled as if it simply grows in line with inflation or folds neatly into traditional 4% rule planning.

Early retirement is a privilege. Planning for it responsibly means acknowledging its unique risks rather than outsourcing them to assumptions that may not hold.

Note: I am not a financial planner, and certainly not your financial planner. I am a podcaster and writer, and this analysis is for educational purposes only. It relies on averages and simplified models. You may reasonably choose to plan more conservatively or more aggressively depending on your circumstances. My goal here is to highlight a real and underappreciated risk while preserving the rational optimism that FIRE remains a real and attainable goal for millions of people in the United States.

Leave a Reply